Template:Sources for the historicity of Jesus

Template:Jesus Christian sources such as the New Testament books in the Christian Bible, include detailed accounts about Jesus, but scholars differ on the historicity of specific episodes described in the biblical accounts of Jesus.[1] The only two events subject to "almost universal assent" are that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist and was crucified by the order of the Roman Prefect Pontius Pilate.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

To establish the existence of a person without any assumptions, one source from one author (either a supporter or opponent) is needed; for Jesus there are at least 12 independent sources from five authors from supporters and 2 independent sources from two authors from non-supporters, within a century of the crucifixion.[10] Since historical sources on other named individuals from first century Galilee were written by either supporters or enemies, these sources on Jesus cannot be dismissed, and the existence of at least 14 sources from at least 7 authors means there is much more evidence available for Jesus than for any other notable person from 1st century Galilee.[10] Some scholars estimate that there are about 30 independent sources written by 25 authors who attest to Jesus overall.[11] It is notable that some independent sources did not survive, but are broadly referenced directly in the surviving sources themsleves (e.g. Luke) or inferred from modern source analysis.[12]

The letters of Paul are the earliest surviving sources referencing Jesus, and Paul documents personally knowing and interacting with eyewitnesses such as Jesus' own brother James and some of Jesus' closest disciples (e.g. Peter and John) around 36 CE, within a few years of the crucifixion (30 or 33 CE).[13] Paul was a contemporary of Jesus and throughout his letters, a fairly full outline of the life of Jesus on earth can be found.[14][15]

The Gospels are commonly seen as literature that is based on oral traditions, Christian preaching, and Old Testament exegesis with the consensus being that they are a variation of Greco-Roman biography; similar to other ancient works such as Xenophon's Memoirs of Socrates.[16]

Non-Christian sources that are used to study and establish the historicity of Jesus include Jewish sources such as Josephus (Jewish historian and commander in Galilee) and Roman sources such as Tacitus (Roman historian and Senator). These sources are compared to Christian sources such as the Pauline Epistles and the Synoptic Gospels. These sources are usually independent of each other (i.e., Jewish sources do not draw upon Roman sources), and similarities and differences between them are used in the authentication process.[17][18]

From just Paul, Josephus, and Tacitus alone, the existence of Jesus along with the general time and place of his activity can be confirmed.[19]

Non-Christian sources

Key sources

Josephus

Template:Main Template:Quote box Template:Quote box

The writings of the 1st century Romano-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus include references to Jesus and the origins of Christianity.[20][21] Josephus was a Jewish historian and commander in Galille who trained 100,000 men in the region, was in contact with the Sanhedrin, even stationed in Sepphoris for a time, which was 3 miles away from Nazareth, the hometown of Jesus; and so he dwelled with inhabitants who would have known Jesus and may have known participants in the trial of Jesus.[22] Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews, written around 93–94 CE, includes two references to Jesus in Books 18 and 20.[20][23]

Of the two passages, the James passage in Book 20 is used by scholars to support the existence of Jesus, the Testimonium Flavianum in Book 18 his crucifixion.[17] Josephus' James passage attests to the existence of Jesus as a historical person and that some of his contemporaries considered him the Messiah.[17][24] According to Bart Ehrman, Josephus' passage about Jesus was altered by a Christian scribe, including the reference to Jesus as the Messiah.[25]

A textual argument against the authenticity of the James passage is that the use of the term "Christos" there seems unusual for Josephus.[26] An argument based on the flow of the text in the document is that, given that the mention of Jesus appears in the Antiquities before that of the John the Baptist, a Christian interpolator may have inserted it to place Jesus in the text before John.[26] A further argument against the authenticity of the James passage is that it would have read well even without a reference to Jesus.[26]

The passage deals with the death of "James the brother of Jesus" in Jerusalem. Whereas the works of Josephus refer to at least twenty different people with the name Jesus, this passage specifies that this Jesus was the one "who was called Christ".[27][28] Louis Feldman states that this passage, above others, indicates that Josephus did say something about Jesus.[29]

Modern scholarship has almost universally acknowledged the authenticity of the reference in Book 20, Chapter 9, 1 of the Antiquities to "the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James",[30] and considers it as having the highest level of authenticity among the references of Josephus to Christianity.[20][21][31][32][33][34]

The Testimonium Flavianum (meaning the testimony of Flavius [Josephus]) is the name given to the passage found in Book 18, Chapter 3, 3 of the Antiquities in which Josephus describes the condemnation and crucifixion of Jesus at the hands of the Roman authorities.[35][36] Scholars have differing opinions on the total or partial authenticity of the reference in the passage to the execution of Jesus by Pontius Pilate.[20][36] The general scholarly view is that while the Testimonium Flavianum is most likely not authentic in its entirety, it is broadly agreed upon that it originally consisted of an authentic nucleus with a reference to the execution of Jesus by Pilate which was then subject to Christian interpolation.[24][36][37][38][39] Although the exact nature and extent of the Christian redaction remains unclear,[40] there is broad consensus as to what the original text of the Testimonium by Josephus would have looked like.[39] This conventional viewpoint was challenged in 2022 by G. J. Goldberg's paraphrase model of the Testimonium.[41] Using research on Josephus's composition methods, Goldberg demonstrated that the Testimonium can be understood as a paraphrase by Josephus of a text very similar to, if not identical with, Luke's Emmaus narrative (Luke 24:18–24). Goldberg argues that consequently there cannot have been any significant Christian additions to Josephus's version, as they would have no reason to have been consistent with this paraphrase relationship. Furthermore, Goldberg argues that Josephus would have known if his Emmaus-like source was trustworthy or not, and so his Testimonium acceptably attests to the historicity of Jesus.

The references found in Antiquities have no parallel texts in the other work by Josephus such as the Jewish War, written twenty years earlier, but some scholars have provided explanations for their absence, such as that the Antiquities covers a longer time period and that during the twenty-year gap between the writing of the Jewish Wars (Template:Circa) and Antiquities (after 90 CE) Christians had become more important in Rome and were hence given attention in the Antiquities.[42]

A number of variations exist between the statements by Josephus regarding the deaths of James and the New Testament accounts.[43] Scholars generally view these variations as indications that the Josephus passages are not interpolations, because a Christian interpolator would more likely have made them correspond to the Christian traditions.[27][43] Robert Eisenman provides numerous early Christian sources that confirm the Josephus testament, that James was the brother of Jesus.[44]

Tacitus

Template:Main Template:Quote box

The Roman historian and senator Tacitus referred to Christ, his execution by Pontius Pilate and the existence of early Christians in Rome in his final work, Annals (Template:Circa), book 15, chapter 44.[45][46][47] The relevant passage reads: "called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus."

Scholars generally consider Tacitus's reference to the execution of Jesus by Pontius Pilate to be both authentic, and of historical value as an independent Roman source about early Christianity that is in unison with other historical records.[48][49][50][51][52] William L. Portier has stated that the consistency in the references by Tacitus, Josephus and the letters to Emperor Trajan by Pliny the Younger reaffirm the validity of all three accounts.[52]

Tacitus was a patriotic Roman senator and his writings show no sympathy towards Christians.[49][53][54][55] Andreas Köstenberger and separately Robert E. Van Voorst state that the tone of the passage towards Christians is far too negative to have been authored by a Christian scribe—a conclusion shared by John P. Meier[48][56][57] Robert E. Van Voorst states that "of all Roman writers, Tacitus gives us the most precise information about Christ".[48]

John Dominic Crossan considers the passage important in establishing that Jesus existed and was crucified, and states: "That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be, since both Josephus and Tacitus... agree with the Christian accounts on at least that basic fact."[58] Bart D. Ehrman states: "Tacitus's report confirms what we know from other sources, that Jesus was executed by order of the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, sometime during Tiberius's reign."[59] Paul Rhodes Eddy and Gregory A. Boyd state that it is now "firmly established" that Tacitus provides a non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus.[60]

Some scholars have debated the historical value of the passage given that Tacitus does not reveal the source of his information.[61] Gerd Theissen and Annette Merz argue that Tacitus at times had drawn on earlier historical works now lost to us, and he may have used official sources from a Roman archive in this case; however, if Tacitus had been copying from an official source, some scholars would expect him to have labeled Pilate correctly as a prefect rather than a procurator.[62] Theissen and Merz state that Tacitus gives us a description of widespread prejudices against Christianity and a few precise details about "Christus" and Christianity, the source of which remains unclear.[63] However, Paul R. Eddy has stated that given his position as a senator Tacitus was also likely to have had access to official Roman documents of the time and did not need other sources.[64]

Weaver notes that Tacitus spoke of the persecution of Christians, but no other Christian author wrote of this persecution for a hundred years.[65] However, classicists have observed that Nero’s persecution has echos in earlier sources such as 1 Clement from the late 90s AD and that the event is acknowledged in numerous earlier Christian sources from the second half of the second century.[66][67]

Richard Carrier has proposed the fringe idea that the reference is a Christian interpolation, and that Tacitus intended to refer to "Chrestians" as a separate religious group unaffiliated with Christianity.[68][69] However, the majority view is that the terms "Chrestians" and "Christians" are the same group.[70] Classicists observe that Carrier’s thesis is outdated, not supported on textual grounds, nor is there any evidence of this non-Christian group existing and is thus dismissed by classical scholars.[66] Furthermore, in a recent assessment by latinists on the passage, they unanimously deemed the passage authentic and noted that no serious Tacitean scholar believe it to be an interpolation.[66] That the passage is not an interpolation is the consensus.[71]

Scholars have also debated the issue of hearsay in the reference by Tacitus. Charles Guignebert argued that "So long as there is that possibility [that Tacitus is merely echoing what Christians themselves were saying], the passage remains quite worthless".[72] R. T. France states that the Tacitus passage is at best just Tacitus repeating what he had heard through Christians.[73] However, Paul R. Eddy has stated that as Rome's preeminent historian, Tacitus was generally known for checking his sources and was not in the habit of reporting gossip.[64] Tacitus was a member of the Quindecimviri sacris faciundis, a council of priests whose duty it was to supervise foreign religious cults in Rome, which as Van Voorst points out, makes it reasonable to suppose that he would have acquired knowledge of Christian origins through his work with that body.[74]

Relevant sources

Mara bar Serapion

Template:Main Mara (son of Sarapion) was a Stoic philosopher from the Roman province of Syria.[75][76] Sometime between 73 CE and the 3rd century, Mara wrote a letter to his son (also called Sarapion) which may contain an early non-Christian reference to the crucifixion of Jesus.[75][77][78]

The letter refers to the unjust treatment of "three wise men": the murder of Socrates, the burning of Pythagoras, and the execution of "the wise king" of the Jews.[75][76] The author explains that in all three cases the wrongdoing resulted in the future punishment of those responsible by God and that when the wise are oppressed, not only does their wisdom triumph in the end, but God punishes their oppressors.[78]

The letter includes no Christian themes and the author is presumed to be a pagan.[76][77] Some scholars see the reference to the execution of the "wise king" of the Jews as an early non-Christian reference to Jesus.[75][76][77] Criteria that support the non-Christian origin of the letter include the observation that "king of the Jews" was not a Christian title, and that the letter's premise that Jesus lives on through the wisdom of his teachings is in contrast to the Christian concept that Jesus continues to live through his resurrection.[77][78]

Scholars such as Robert Van Voorst see little doubt that the reference to the execution of the "king of the Jews" is about the death of Jesus.[78] Others such as Craig A. Evans see less value in the letter, given its uncertain date, and the possible ambiguity in the reference.[79]

Suetonius

The Roman historian Suetonius (Template:Circa – after 122 CE) made references to early Christians and their leader in his work Lives of the Twelve Caesars (written 121 CE).[75][80][81][82] The references appear in Claudius 25 and Nero 16 which describe the lives of Roman Emperors Claudius and Nero.[80] The Nero 16 passage refers to the abuses by Nero and mentions how he inflicted punishment on Christians—which is generally dated to around 64 CE.[83] This passage shows the clear contempt of Suetonius for Christians - the same contempt expressed by Tacitus and Pliny the Younger in their writings, but does not refer to Jesus himself.[81]

The earlier passage in Claudius may include a reference to Jesus, but is subject to debate among scholars.[82] In Claudius 25 Suetonius refers to the expulsion of Jews by Claudius and states:[80]

- "Since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he expelled them from Rome."

The reference in Claudius 25 involves the agitations in the Jewish community which led to the expulsion of some Jews from Rome by Claudius, and is likely the same event mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles (18:2).[75] Most historians date this expulsion to around 49–50 CE.[75][84] Suetonius refers to the leader of the Christians as Chrestus, a term also used by Tacitus, referred in Latin dictionaries as a (amongst other things) version of 'Christus'.[85] However, the wording used by Suetonius implies that Chrestus was alive at the time of the disturbance and was agitating the Jews in Rome.[39][75] This weakens the historical value of his reference as a whole, and there is no overall scholarly agreement about its value as a reference to Jesus.[39][82] However, the confusion of Suetonius also points to the lack of Christian interpolation, for a Christian scribe would not have confused the Jews with Christians.[39][82]

Most scholars assume that in the reference Jesus is meant and that the disturbances mentioned were due to the spread of Christianity in Rome.[82][86][87] However, scholars are divided on the value of the Suetonius' reference. Some scholars such as Craig A. Evans, John Meier and Craig S. Keener see it as a likely reference to Jesus.[88][89] Others such as Stephen Benko and H. Dixon Slingerland see it as having little or no historical value.[82]

Menahem Stern states Suetonius definitely was referring to Jesus; because he would have added "a certain" to Chrestus if he had meant some unknown agitator.[90]

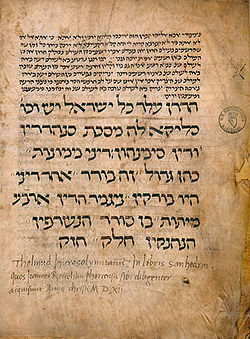

Template:AnchorThe Talmud

The Babylonian Talmud in a few cases includes possible references to Jesus using the terms "Yeshu", "Yeshu ha-Notzri", "ben Stada", and "ben Pandera". Some of these references probably date back to the Tannaitic period (70–200 CE).[91][92] In some cases, it is not clear if the references are to Jesus, or other people, and scholars continue to debate their historical value, and exactly which references, if any, may be to Jesus.[93][94][95]

Robert Van Voorst states that the scarcity of Jewish references to Jesus is not surprising, given that Jesus was not a prominent issue for the Jews during the first century, and after the devastation caused by the Siege of Jerusalem in the year 70, Jewish scholars were focusing on preserving Judaism itself, rather than paying much attention to Christianity.[96]

Robert Eisenman argues that the derivation of Jesus of Nazareth from "ha-Notzri" is impossible on etymological grounds, as it would suggest rather "the Nazirite" rather than "the Nazarene".[97]

Van Voorst states that although the question of who was referred to in various points in the Talmud remains subject to debate among scholars, in the case of Sanhedrin 43a (generally considered the most important reference to Jesus in rabbinic literature), Jesus can be confirmed as the subject of the passage, not only from the reference itself, but from the context that surrounds it, and there is little doubt that it refers to the death of Jesus of Nazareth.[98][99] Christopher M. Tuckett states that if it is accepted that death narrative of Sanhedrin 43a refers to Jesus of Nazareth then it provides evidence of Jesus' existence and execution.[100]

Andreas Kostenberger states that the passage is a Tannaitic reference to the trial and death of Jesus at Passover and is most likely earlier than other references to Jesus in the Talmud.[92] The passage reflects hostility toward Jesus among the rabbis and includes this text:[91][92]

It is taught: On the eve of Passover they hung Yeshu and the crier went forth for forty days beforehand declaring that "[Yeshu] is going to be stoned for practicing witchcraft, for enticing and leading Israel astray. Anyone who knows something to clear him should come forth and exonerate him." But no one had anything exonerating for him and they hung him on the eve of Passover.[101]

Peter Schäfer states that there can be no doubt that the narrative of the execution of Jesus in the Talmud refers to Jesus of Nazareth, but states that the rabbinic literature in question are not Tannaitic but from a later Amoraic period and may have drawn on the Christian gospels, and may have been written as responses to them.[102] Bart Ehrman and separately Mark Allan Powell state that given that the Talmud references are quite late, they can give no historically reliable information about the teachings or actions of Jesus during his life.[103][104]

Another reference in early second century Rabbinic literature (Tosefta Hullin II 22) refers to Rabbi Eleazar ben Dama who was bitten by a snake, but was denied healing in the name of Jesus by another Rabbi for it was against the law, and thus died.[105] This passage reflects the attitude of Jesus' early Jewish opponents, i.e. that his miracles were based on evil powers.[105][106]

Eddy and Boyd, who question the value of several of the Talmudic references state that the significance of the Talmud to historical Jesus research is that it never denies the existence of Jesus, but accuses him of sorcery, thus indirectly confirming his existence.[93] R. T. France and separately Edgar V. McKnight state that the divergence of the Talmud statements from the Christian accounts and their negative nature indicate that they are about a person who existed.[107][108] Craig Blomberg states that the denial of the existence of Jesus was never part of the Jewish tradition, which instead accused him of being a sorcerer and magician, as also reflected in other sources such as Celsus.[91] Andreas Kostenberger states that the overall conclusion that can be drawn from the references in the Talmud is that Jesus was a historical person whose existence was never denied by the Jewish tradition, which instead focused on discrediting him.[92]

Minor sources

Pliny the Younger (Template:Circa), the provincial governor of Pontus and Bithynia, wrote to Emperor Trajan c. 112 concerning how to deal with Christians, who refused to worship the emperor, and instead worshiped "Christus". Charles Guignebert, who does not doubt that Jesus of the Gospels lived in Gallilee in the 1st century, nevertheless dismisses this letter as acceptable evidence for a historical Jesus.[109]

Thallus, of whom very little is known, and none of whose writings survive, wrote a history allegedly around the middle to late first century CE, to which Eusebius referred. Julius Africanus, writing Template:Circa, links a reference in the third book of the History to the period of darkness described in the crucifixion accounts in three of the Gospels.[110][111] It is not known whether Thallus made any mention to the crucifixion accounts; if he did and the dating is accurate, it would be the earliest noncanonical reference to a gospel episode, but its usefulness in determining the historicity of Jesus is uncertain.[110][112][113]

Phlegon of Tralles, 80–140 CE: similar to Thallus, Julius Africanus mentions a historian named Phlegon who wrote a chronicle of history around 140 CE, where he records: "Phlegon records that, in the time of Tiberius Caesar, at full moon, there was a full eclipse of the sun from the sixth to the ninth hour." (Africanus, Chronography, 18:1) Phlegon is also mentioned by Origen (an early church theologian and scholar, born in Alexandria): "Now Phlegon, in the thirteenth or fourteenth book, I think, of his Chronicles, not only ascribed to Jesus a knowledge of future events ... but also testified that the result corresponded to His predictions." (Origen Against Celsus, Book 2, Chapter 14) "And with regard to the eclipse in the time of Tiberius Caesar, in whose reign Jesus appears to have been crucified, and the great earthquakes which then took place ..." (Origen Against Celsus, Book 2, Chapter 33) "Jesus, while alive, was of no assistance to himself, but that he arose after death, and exhibited the marks of his punishment, and showed how his hands had been pierced by nails." (Origen Against Celsus, Book 2, Chapter 59).[114]

Philo, who dies after 40 CE, is mainly important for the light he throws on certain modes of thought and phraseology found again in some of the Apostles. Eusebius[115] indeed preserves a legend that Philo had met Peter in Rome during his mission to the Emperor Caius; moreover, that in his work on the contemplative life he describes the life of the Church of Alexandria, rather than that of the Essenes and Therapeutae. But it is hardly probable that Philo had heard enough of Jesus and His followers to give an historical foundation to the foregoing legends.[116]

Celsus writing late in the second century produced the first full-scale attack on Christianity.[110][117] Celsus' document has not survived but in the third century Origen replied to it, and what is known of Celsus' writing is through the responses of Origen.[110] According to Origen, Celsus accused Jesus of being a magician and a sorcerer. While the statements of Celsus may be seen as valuable, they have little historical value, given that the wording of the original writings can not be examined.[117]

The Dead Sea Scrolls are first century or older writings that show the language and customs of some Jews of Jesus' time.[118] Scholars such as Henry Chadwick see the similar uses of languages and viewpoints recorded in the New Testament and the Dead Sea Scrolls as valuable in showing that the New Testament portrays the first century period that it reports and is not a product of a later period.[119][120] However, the relationship between the Dead Sea scrolls and the historicity of Jesus has been the subject of highly controversial theories, and although new theories continue to appear, there is no overall scholarly agreement about their impact on the historicity of Jesus, despite the usefulness of the scrolls in shedding light on first-century Jewish traditions.[121][122]

Disputed sources

The following sources are disputed, and of limited historical value:

- Lucian of Samosata (born 115 CE), a well-known Greek satirist and traveling lecturer wrote mockingly of the followers of Jesus for their ignorance and credulity.[110][123] Given that Lucian's understanding of Christian traditions has significant gaps and errors, his writing is unlikely to have been influenced by Christians themselves, and he may provide an independent statement about the crucifixion of Jesus.[110] However, given the nature of the text as satire, Lucian may have embellished the stories he heard and his account cannot have a high degree of historical reliability.[123]

- Emperor Trajan (Template:Circa–117), in reply to a letter sent by Pliny the Younger, wrote "You observed proper procedure, my dear Pliny, in sifting the cases of those who had been denounced to you as Christians. For it is not possible to lay down any general rule to serve as a kind of fixed standard. They are not to be sought out; if they are denounced and proved guilty, they are to be punished, with this reservation, that whoever denies that he is a Christian and really proves it—that is, by worshiping our gods—even though he was under suspicion in the past, shall obtain pardon through repentance. But anonymously posted accusations ought to have no place in any prosecution. For this is both a dangerous kind of precedent and out of keeping with the spirit of our age."

- Epictetus (55–135 CE) provides another possible yet disputed reference to Christians as "Galileans" in his "Discourses" 4.7.6 and 2.9.19–21: "Therefore, if madness can produce this attitude [of detachment] toward these things [death, loss of family, property], and also habit, as with the Galileans, can no one learn from reason and demonstration that God has made all things in the universe, and the whole universe itself, to be unhindered and complete in itself, and the parts of it to serve the needs of the whole."

- Numenius of Apamea, in the second century, wrote a possible allusion to Christians and Christ that is contained in fragments of his treatises on the points of divergence between the Academicians and Plato, on the Good (in which according to Origen, Contra Celsum, iv. 51, he makes an allusion to Jesus Christ).[124]

- Claudius Galenus (Galen) (129–200 CE) may reference Christ and his followers; From Galen, De differentiis pulsuum (On the pulse), iii, 3. The work is listed in De libris propriis 5, and seems to belong between 176 and 192 CE, or possibly even 176–180: "One might more easily teach novelties to the followers of Moses and Christ than to the physicians and philosophers who cling fast to their schools".[125]

- Tertullian (155–220) suggests in book 4 of his work, Against Marcion, the existence of Census records for a census taken during the time of Gaius Sentius Saturninus, which corroberates Jesus's birth during this time.[126] However these records have not resurfaced. Additionally, in Apologeticus, he refers to records from the Roman Archives which back up the account of the Crucifixion darkness from the bible. These records however, have not resurfaced.[127]

- Abgar-Tiberius Correspondence: Ilaria Ramelli argues that the earliest documents to discuss Jesus are an exchange of letters between the Roman Emperor Tiberius and the king of Osroene Abgar V discussing political developments in the region near Parthia.[128] The authenticity of the correspondence is disputed by many scholars.

James Ossuary

Template:Main There is a limestone burial box from the 1st century known as the James Ossuary with the Aramaic inscription, "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus." The authenticity of the inscription was challenged by the Israel Antiquities Authority, who filed a complaint with the Israeli police. In 2012, the owner of the ossuary was found not guilty, with the judge ruling that the authenticity of the ossuary inscription had not been proven either way.[129] It has been suggested it was a forgery.[130]

Christian sources

Various books, memoirs and stories were written about Jesus by the early Christians. The most famous are the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. All but one of these are believed to have been written within 50–70 years of the death of Jesus, with the Gospel of Mark believed to be the earliest, and the last the Gospel of John.[131][132] According to critical scholars such as Bart Ehrman and Robert Eisenman the gospels were written by Christians decades after Jesus' death, by authors who had not witnessed any events in Jesus' life.[133][134] Ehrman elucidates that all four gospels present Jesus as man who was understood to be divine.[135] However, according to Maurice Casey, some of the Gospel sources are early Aramaic sources which indicate proximity with eyewitness testimony.[136] Furthermore, Ehrman observes that the surviving Gospels show usage of much earlier independent written and oral sources that extended back to the time of Jesus death around 29 or 30 CE, but did not survive; and that Luke's observation that many sources existed by his time is accurate.[137]

Blainey writes that the oldest surviving record written by an early Christian is a short letter by St Paul: the First Epistle to the Thessalonians, which appeared about 25 years after the death of Jesus.[138] Ehrman observes that Paul in his letters does document interactions with eyewitnesses of Jesus life such as the apostle Peter, James the brother of Jesus,[13][139] and John.[139] Paul was personally acquainted with them and the earliest meeting with Peter and James specifically occurred in 36 CE.[13]

Pauline epistles

Overview

Paul's letters (generally dated to circa 48–62 CE) are the earliest surviving sources on Jesus.[140][141][142] Paul was not a companion of Jesus.[143] However, Paul was a contemporary of Jesus and states that he personally knew and interacted with eyewitnesses of Jesus such as his most intimate disciples (Peter and John) and family members (his brother James) starting around 36 AD, and got some direct information from them.[13][144] In the context of Christian sources, even if all other texts are ignored, the Pauline epistles can provide some information regarding Jesus.[7][145] This information does not include all details found in the Gospels, but it does provide some significant details and refers to his existence as a person.[146] This information comes from those letters of Paul whose authenticity is not disputed.[145] From Paul's writings alone, a fairly full outline of the life of Jesus can found: his descent from Abraham and David, his upbringing in the Jewish Law, gathering together disciples, including Cephas (Peter) and John, having a brother named James, living an exemplary life, the Last Supper and betrayal, numerous details surrounding his death and resurrection (e.g. crucifixion, Jewish involvement in putting him to death, burial, resurrection, seen by Peter, James, the twelve and others) along with numerous quotations referring to notable teachings and events found in the Gospels.[147][148]

Of the thirteen letters that bear Paul's name, seven are considered authentic by almost all scholars, and the others are generally considered pseudepigraphic.[149][150][151][152] The 7 undisputed letters (and their approximate dates) are: Galatians (Template:Circa CE), 1 Thessalonians (Template:Circa-51 CE), 1 Corinthians (Template:Circa–54 CE), 2 Corinthians (Template:Circa–56 CE), Romans (Template:Circa–57 CE), Philippians (Template:Circa–59 or 62 CE), Philemon (Template:Circa–59 or 62 CE).[149][151][152] The authenticity of these letters is accepted by almost all scholars, and they have been referenced and interpreted by early authors such as Origen and Eusebius.[150][153]

Given that the Pauline epistles are generally dated 50–60 CE, they are the earliest surviving Christian texts that include information about Jesus.[152] These letters were written approximately twenty to thirty years after the generally accepted time period for the death of Jesus, around 30–36 CE.[152] The letters were written during a time when Paul recorded encounters with eyewitnesses such as disciples of Jesus, e.g. Galatians 1:18 states that three years after his conversion Paul went to Jerusalem and stayed with Apostle Peter for fifteen days.[152] According to Buetz, during this time Paul disputed the nature of Jesus' message with Jesus' brother James, concerning the importance of adhering to kosher food restrictions and circumcision, important features of determining Jewish identity.[154][155] The New Testament narratives, however, do not give any details about what they discussed at that time; fourteen years after that meeting, Paul returned to Jerusalem to confirm that his teaching was orthodox, as part of the Council of Jerusalem.

The Pauline letters were not intended to provide a narrative of the life of Jesus, but were written as expositions of Christian teachings.[152][156] In Paul's view, the earthly life of Jesus was of lower importance than the theology of his death and resurrection, a theme that permeates Pauline writings.[157] However, the Pauline letters clearly indicate that for Paul, Jesus was a real person (born of a woman as in Gal 4.4), a Jew ("born under the law", Romans 1.3) who had disciples (1 Corinthians 15.5), who was crucified (as in 1 Corinthians 2.2 and Galatians 3.1) and later resurrected (1 Corinthians 15.20, Romans 1.4 and 6.5, Philippians 3:10–11).[7][145][152][157] The letters reflect the general concept within the early Gentillic Christian Church that Jesus existed, was crucified and later raised from the dead.[7][152]

The references by Paul establish the main outline of Jesus life indicative that the existence of Jesus was the accepted norm within the early Christians (including the Christian community in Jerusalem, given the references to collections there) within twenty years after the death of Jesus, at a time when those who could have been acquainted with him could still be alive.[158][159]

Specific references

The seven Pauline epistles that are widely regarded as authentic include the following information that along with other historical elements are used to study the historicity of Jesus:[7][145]

- Existence of Jesus: That in Paul's view Jesus existed and was a Jew is based on Galatians 4:4 which states that he was "born of a woman" and Romans 1:3 that he was "born under the law".[7][145][160] Some scholars such as Paul Barnett hold that this indicates that Paul had some familiarity with the circumstances of the birth of Jesus, but that is not shared among scholars in general.[156][161] However, the statement does indicate that Paul had some knowledge of and interest in Jesus' life before his crucifixion.[156]

- Disciples and brothers: 1 Corinthians 15:5 states that Paul knew that Jesus had 12 disciples, and considers Peter as one of them.[7][160][162] 1 Corinthians 1:12 further indicates that Peter was known in Corinth before the writing of 1 Corinthians, for it assumes that they were familiar with Cephas/Peter.[163][164] The statement in 1 Corinthians 15:5 indicates that "the twelve" as a reference to the twelve apostles was a generally known notion within the early Christian Church in Corinth and required no further explanation from Paul.[165] Galatians 1:18 further states that Paul personally knew Peter and stayed with him in Jerusalem for fifteen days, about three years after his conversion.[166] It also implies that Peter was already known to the Galatians and required no introduction.[167] 1 Corinthians 9:5 and Galatians 1:19 state that Jesus had brothers, one being called James, whom Paul met or "saw."[7][146][160] James was claimed by early Christian writers as Origen and Eusebius to have been the leader of the followers of Jesus, after his brother's death, and to have been the first bishop, or bishop of bishops in Jerusalem.

- Betrayal and rituals: That Jesus was betrayed and established some traditions such as the Eucharist are derived from 1 Corinthians 11:23–25 which states: "The Lord Jesus in the night in which he was betrayed took bread; and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, This is my body, which is for you: this do in remembrance of me.".[7][160]

- Crucifixion: The Pauline letters include several references to the crucifixion of Jesus e.g. 1 Corinthians 1:23, 1 Corinthians 2:2 and Galatians 3:1 among others.[7][160] The death of Jesus forms a central element of the Pauline letters.[157] 1 Thessalonians 2:15 places the responsibility for the death of Jesus on some Jews.[7][160] Moreover, the statement in 1 Thessalonians 2:14–16 about the Jews "who both killed the Lord Jesus" and "drove out us" indicates that the death of Jesus was within the same time frame as the persecution of Paul.[168]

- Burial: 1 Corinthians 15:4 and Romans 6:4 state that following his death Jesus was buried.[160] This reference is then used by Paul to build on the theology of resurrection, but reflects the common belief at the time that Jesus was buried after his death.[169][170]

The existence of only these references to Jesus in the Pauline epistles has given rise to criticism of them by G. A. Wells, who is generally accepted as a leader of the movement to deny the historicity of Jesus.[171][172] When Wells was still denying the existence of Jesus, he criticized the Pauline epistles for not mentioning items such as John the Baptist or Judas or the trial of Jesus and used that argument to conclude that Jesus was not a historical figure.[171][172][173]

James D. G. Dunn addressed Wells' statement and stated that he knew of no other scholar that shared that view, and most other scholars had other and more plausible explanations for the fact that Paul did not include a narrative of the life of Jesus in his letters, which were primarily written as religious documents rather than historical chronicles at a time when the life story of Jesus could have been well known within the early Church.[173] Dunn states that despite Wells' arguments, the theories of the non-existence of Jesus are a "thoroughly dead thesis".[157]

While Wells no longer denies the existence of Jesus, he has responded to Dunn, stating that his arguments from silence not only apply to Paul but all early Christian authors, and that he still has a low opinion of early Christian texts, maintaining that for Paul Jesus may have existed a good number of decades before.[171]

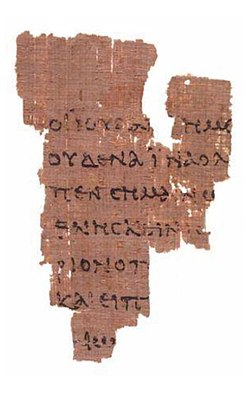

Pre-Pauline creeds

Template:Main The Pauline letters sometimes refer to creeds, or confessions of faith, that predate their writings.[174][175][176] For instance 1 Corinthians 15:3–4 reads: "For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures."[174] Romans 1:3–4 refers to Romans 1:2 just before it which mentions an existing gospel, and in effect may be treating it as an earlier creed.[174][175]

One of the keys to identifying a pre-Pauline tradition is given in 1 Corinthians 15:11[176]

- Whether then [it be] I or they, so we preach, and so ye believed.

Here Paul refers to others before him who preached the creed.[176] James Dunn states that 1 Corinthians 15:3 indicates that in the 30s Paul was taught about the death of Jesus a few years earlier.[177]

The Pauline letters thus contain Christian creed elements of pre-Pauline origin.[178] The antiquity of the creed has been located by many biblical scholars to less than a decade after Jesus' death, originating from the Jerusalem apostolic community.[179] Concerning this creed, Campenhausen wrote, "This account meets all the demands of historical reliability that could possibly be made of such a text,"[180] whilst A. M. Hunter said, "The passage therefore preserves uniquely early and verifiable testimony. It meets every reasonable demand of historical reliability."[181]

These creeds date to within a few years of Jesus' death, and developed within the Christian community in Jerusalem.[182] Although embedded within the texts of the New Testament, these creeds are a distinct source for Early Christianity.[175] This indicates that existence and death of Jesus was part of Christian belief a few years after his death and over a decade before the writing of the Pauline epistles.[182]

Gospels

The four canonical gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are the main sources for the biography of Jesus' life, the teachings and actions attributed to him.[183][184][185] Three of these (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) are known as the synoptic Gospels, from the Greek σύν (syn "together") and ὄψις (opsis "view"), given that they display a high degree of similarity in content, narrative arrangement, language and paragraph structure.[186][187] The presentation in the fourth canonical gospel, i.e. John, differs from these three in that it has more of a thematic nature rather than a narrative format.[188] Scholars generally agree that it is impossible to find any direct literary relationship between the synoptic gospels and the Gospel of John.[188]

The authors of the New Testament generally showed little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life with the secular history of the age.[189] The gospels were primarily written as theological documents in the context of early Christianity with the chronological timelines as a secondary consideration.[190] One manifestation of the gospels being theological documents rather than historical chronicles is that they devote about one third of their text to just seven days, namely the last week of the life of Jesus in Jerusalem.[191] Although the gospels do not provide enough details to satisfy the demands of modern historians regarding exact dates, scholars have used them to reconstruct a number of portraits of Jesus.[189][190][192] However, as stated in John 21:25 the gospels do not claim to provide an exhaustive list of the events in the life of Jesus.[193]

Scholars have varying degrees of certainty about the historical reliability of the accounts in the gospels, and the only two events whose historicity is the subject of almost universal agreement among scholars are the baptism and crucifixion of Jesus.[3] Scholars such as E.P. Sanders and separately Craig A. Evans go further and assume that two other events in the gospels are historically certain, namely that Jesus called disciples, and caused a controversy at the Temple.[9]

Ever since the Augustinian hypothesis, scholars continue to debate the order in which the gospels were written, and how they may have influenced each other, and several hypotheses exist in that regard, e.g. the Markan priority hypothesis holds that the Gospel of Mark was written first Template:Circa.[194][195] In this approach, Matthew is placed at being sometime after this date and Luke is thought to have been written between 70 and 100 CE.[196] However, according to the competing, and more popular, Q source hypothesis, the gospels were not independently written, but were derived from a common source called Q.[197][198] The two-source hypothesis then proposes that the authors of Matthew and Luke drew on the Gospel of Mark as well as on Q.[199]

The gospels can be seen as having three separate lines: A literary line which looks at it from a textual perspective, secondly a historical line which observes how Christianity started as a renewal movement within Judaism and eventually separated from it, and finally a theological line which analyzes Christian teachings.[200] Within the historical perspective, the gospels are not simply used to establish the existence of Jesus as sources in their own right alone, but their content is compared and contrasted to non-Christian sources, and the historical context, to draw conclusions about the historicity of Jesus.[7][24][201]

Early Church fathers

Two possible patristic sources that may refer to eyewitness encounters with Jesus are the early references of Papias and Quadratus, reported by Eusebius of Caesarea in the 4th century.[202][203]

The works of Papias have not survived, but Eusebius quotes him as saying:[202]

- "...if by chance anyone who had been in attendance on the elders should come my way, I inquired about the words of the elders—that is, what according to the elders Andrew or Peter said, or Philip, or Thomas or James, or John or Matthew or any other of the Lord’s disciples, and whatever Aristion and the elder John, the Lord’s disciples, were saying."

Richard Bauckham states that while Papias was collecting his information (Template:Circa), Aristion and the elder John (who were Jesus' disciples) were still alive and teaching in Asia minor, and Papias gathered information from people who had known them.[202] However, the exact identity of the "elder John" is wound up in the debate on the authorship of the Gospel of John, and scholars have differing opinions on that, e.g. Jack Finegan states that Eusebius may have misunderstood what Papias wrote, and the elder John may be a different person from the author of the fourth gospel, yet still a disciple of Jesus.[204] Gary Burge, on the other hand sees confusion on the part of Eusebius and holds the elder John to be different person from the apostle John.[205]

The letter of Quadratus (possibly the first Christian apologist) to emperor Hadrian (who reigned 117–138) is likely to have an early date and is reported by Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History 4.3.2 to have stated:[206]

- "The words of our Savior were always present, for they were true: those who were healed, those who rose from the dead, those who were not only seen in the act of being healed or raised, but were also always present, not merely when the Savior was living on earth, but also for a considerable time after his departure, so that some of them survived even to our own times."[207]

By "our Savior" Quadratus means Jesus and the letter is most likely written before 124 CE.[203] Bauckham states that by "our times" he may refer to his early life, rather than when he wrote (117–124), which would be a reference contemporary with Papias.[208] Bauckham states that the importance of the statement attributed to Quadratus is that he emphasizes the "eye witness" nature of the testimonies to interaction with Jesus.[207] Such "eye witness statements" abound in early Christian writings, particularly the pseudonymous Christian Apocrypha, Gospels and Letters, in order to give them credibility.

Apocryphal texts

Template:See also A number of later Christian texts, usually dating to the second century or later, exist as New Testament apocrypha, among which the gnostic gospels have been of major recent interest among scholars.[209] The 1945 discovery of the Nag Hammadi library created a significant amount of scholarly interest and many modern scholars have since studied the gnostic gospels and written about them.[210] However, the trend among the 21st century scholars has been to accept that while the gnostic gospels may shed light on the progression of early Christian beliefs, they offer very little to contribute to the study of the historicity of Jesus, in that they are rather late writings, usually consisting of sayings (rather than narrative, similar to the hypothesised Q documents), their authenticity and authorship remain questionable, and various parts of them rely on components of the New Testament.[210][211] The focus of modern research into the historical Jesus has been away from gnostic writings and towards the comparison of Jewish, Greco-Roman and canonical Christian sources.[210][211]

As an example, Bart Ehrman states that gnostic writings of the Gospel of Thomas (part of the Nag Hammadi library) have very little value in historical Jesus research, because the author of that gospel placed no importance on the physical experiences of Jesus (e.g. his crucifixion) or the physical existence of believers, and was only interested in the secret teachings of Jesus rather than any physical events.[211] Similarly, the Apocryphon of John (also part of the Nag Hammadi library) has been useful in studying the prevailing attitudes in the second century, and questions of authorship regarding the Book of revelation, given that it refers to Revelation 1:19, but is mostly about the post ascension teachings of Jesus in a vision, not a narrative of his life.[212] Some scholars such as Edward Arnal contend that the Gospel of Thomas continues to remain useful for understanding how the teachings of Jesus were transmitted among early Christians, and sheds light on the development of early Christianity.[213]

There is overlap between the sayings of Jesus in the apocryphal texts and canonical Christian writings, and those not present in the canonical texts are called agrapha. There are at least 225 agrapha but most scholars who have studied them have drawn negative conclusions about the authenticity of most of them and see little value in using them for historical Jesus research.[214] Robert Van Voorst states that the vast majority of the agrapha are certainly inauthentic.[214] Scholars differ on the number of authentic agrapha, some estimating as low as seven as authentic, others as high as 18 among the more than 200, rendering them of little value altogether.[214] While research on apocryphal texts continues, the general scholarly opinion holds that they have little to offer to the study of the historicity of Jesus given that they are often of uncertain origin, and almost always later documents of lower value.[209]

See also

- Christ myth theory

- Census of Quirinius, the enrollment of the Roman provinces of Syria and Judaea for tax purposes taken in the year 6/7.

- Cultural and historical background of Jesus

- Historical Jesus

- Historical reliability of the Gospels

- Quest for the historical Jesus

- The Bible and history

Notes

References

- Brown, Raymond E. (1997) An Introduction to the New Testament. Doubleday Template:ISBN

- Daniel Boyarin (2004). Border Lines. The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Doherty, Earl (1999). The Jesus Puzzle. Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ? : Challenging the Existence of an Historical Jesus. Template:ISBN

- Drews, Arthur & Burns, C. Deslisle (1998). The Christ Myth (Westminster College–Oxford Classics in the Study of Religion). Template:ISBN

- Ellegård, Alvar Jesus – One Hundred Years Before Christ: A Study in Creative Mythology, (London 1999).

- France, R.T. (2001). The Evidence for Jesus. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Freke, Timothy & Gandy, Peter. The Jesus Mysteries – was the original Jesus a pagan god? Template:ISBN

- George, Augustin & Grelot, Pierre (Eds.) (1992). Introducción Crítica al Nuevo Testamento. Herder. Template:ISBN

- Template:Cite book

- Gowler, David B. (2007). What Are They Saying About the Historical Jesus?. Paulist Press.

- Grant, Michael, Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels, Scribner, 1995. Template:ISBN

- Meier, John P., A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Anchor Bible Reference Library, Doubleday

- (1991), v. 1, The Roots of the Problem and the Person, Template:ISBN

- (1994), v. 2, Mentor, Message, and Miracles, Template:ISBN

- (2001), v. 3, Companions and Competitors, Template:ISBN

- (2009), v. 4, Law and Love, Template:ISBN

- Mendenhall, George E. (2001). Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context. Template:ISBN

- Messori, Vittorio (1977). Jesus hypotheses. St Paul Publications. Template:ISBN

- Mykytiuk, Lawrence (2015). "Did Jesus Exist? Searching for Evidence Beyond the Bible." Biblical Archaeology Society, Bible History Daily section. December 2014. http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/people-cultures-in-the-bible/jesus-historical-jesus/did-jesus-exist/

- New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha, New Revised Standard Version. (1991) New York, Oxford University Press. Template:ISBN

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Wells, George A. (1988). The Historical Evidence for Jesus. Prometheus Books. Template:ISBN

- Wells, George A. (1998). The Jesus Myth. Template:ISBN

- Wells, George A. (2004). Can We Trust the New Testament?: Thoughts on the Reliability of Early Christian Testimony. Template:ISBN

- Wilson, Ian (2000). Jesus: The Evidence (1st ed.). Regnery Publishing.

Template:Jesus footerTemplate:HistoricityTemplate:The Bible and history

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Template:Cite book States that baptism and crucifixion are "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent".

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 Baker Academic Template:ISBN pp. 441-442

- ↑ Eddy, Paul; Boyd, Gregory (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Template:ISBN pp. 202, 209-228

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Feldman, Louis H.; Hata, Gōhei, eds. (1987). Josephus, Judaism and Christianity BRILL. Template:ISBN. pp. 54–57

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Maier, Paul L. (December 1995). Josephus, the essential works: a condensation of Jewish antiquities and The Jewish war. Kregel Academic. Template:ISBN pp. 284–285

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Maier, Paul L. (December 1995). Josephus, the essential works: a condensation of Jewish antiquities and The Jewish war. Kregel Academic. Template:ISBN p. 12

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Kostenberger, Andreas J.; Kellum, L. Scott; Quarles, Charles L. (2009). The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament Template:ISBN pp. 104–105

- ↑ Bart Ehrman, Jesus Interrupted, p. 159, Harper Collins

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Eddy, Paul; Boyd, Gregory (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Template:ISBN pp. 128–130

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Eddy, Paul; Boyd, Gregory (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Template:ISBN pp. 129–130

- ↑ Painter, John (2005). Just James: The Brother of Jesus in History and Tradition. Template:ISBN p. 137

- ↑ Feldman, Louis H.; Hata, Gōhei. Josephus, Judaism and Christianity. Brill. Template:ISBN. p. 56

- ↑ Louis Feldman (Template:ISBN pp. 55–57) states that the authenticity of the Josephus passage on James has been "almost universally acknowledged".

- ↑ Van Voorst, Robert E. (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.. Template:ISBN p. 83

- ↑ Richard Bauckham "For What Offense Was James Put to Death?" in James the Just and Christian origins by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1999 Template:ISBN pp. 199–203

- ↑ Painter, John (2005). Just James: The Brother of Jesus in History and Tradition. Template:ISBN pp. 134–141

- ↑ Sample quotes from previous references: Van Voorst (Template:ISBN p. 83) states that the overwhelming majority of scholars consider both the reference to "the brother of Jesus called Christ" and the entire passage that includes it as authentic." Bauckham (Template:ISBN pp. 199–203) states: "the vast majority have considered it to be authentic". Meir (Template:ISBN pp. 108–109) agrees with Feldman that few have questioned the authenticity of the James passage. Setzer (Template:ISBN pp. 108–109) also states that few have questioned its authenticity.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus; Whiston, William; Maier, Paul L. (May 1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Academic. Template:ISBN p. 662

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Schreckenberg, Heinz; Schubert, Kurt (1992a). Jewish Traditions in Early Christian Literature. 2. Template:ISBN pp. 38–41

- ↑ Evans, Craig A. (2001). Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies Template:ISBN p. 316

- ↑ Wansbrough, Henry (2004). Jesus and the oral Gospel tradition. Template:ISBN p. 185

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 Jesus Remembered by James D. G. Dunn 2003 Template:ISBN pp. 141–143

- ↑ Wilhelm Schneemelcher, Robert McLachlan Wilson, New Testament Apocrypha: Gospels and Related Writings, p. 490 (James Clarke & Co. Ltd, 2003). Template:ISBN

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2172: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Feldman, Louis H. (1984). "Flavius Josephus Revisited: The Man, his Writings and his Significance". In Temporini, Hildegard; Haase, Wolfgang. Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, Part 2. pp. 763–771. Template:ISBN p. 826

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Painter, John (2005). Just James: The Brother of Jesus in History and Tradition. Template:ISBN pp. 143–145

- ↑ Eisenman, Robert (2002), "James the Brother of Jesus: the key to unlocking the secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls" (Watkins)

- ↑ P. E. Easterling, E. J. Kenney (general editors), The Cambridge History of Latin Literature, p. 892 (Cambridge University Press, 1982, reprinted 1996). Template:ISBN

- ↑ A political history of early Christianity by Allen Brent 2009 Template:ISBN pp. 32–34

- ↑ Robert Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000. pp. 39–53

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000. pp. 39–53

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies by Craig A. Evans 2001 Template:ISBN p. 42

- ↑ Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 2001 Template:ISBN p. 343

- ↑ Pontius Pilate in History and Interpretation by Helen K. Bond 2004 Template:ISBN p. xi

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Tradition and Incarnation: Foundations of Christian Theology by William L. Portier 1993 Template:ISBN p. 263

- ↑ Ancient Rome by William E. Dunstan 2010 Template:ISBN p. 293

- ↑ Jesus as a figure in history: how modern historians view the man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell 1998 Template:ISBN p. 33

- ↑ An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity by Delbert Royce Burkett 2002 Template:ISBN p. 485

- ↑ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 Template:ISBN p. 109–110

- ↑ Meier, John P., A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Doubleday: 1991. vol 1: pp. 168–171.

- ↑ Crossan, John Dominic (1995). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. HarperOne. Template:ISBN p. 145

- ↑ Ehrman p 212

- ↑ Eddy, Paul; Boyd, Gregory (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition Baker Academic, Template:ISBN p. 127

- ↑ F.F. Bruce,Jesus and Christian Origins Outside the New Testament, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974) p. 23

- ↑ Theissen and Merz p.83

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 The Jesus legend: a case for the historical reliability of the synoptic gospels by Paul R. Eddy, et al 2007 Template:ISBN pp. 181–183

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Jones, Christopher P. "The Historicity of the Neronian Persecution: A Response to Brent Shaw." New Testament Studies 63.1 (2017): 146-152.

- ↑ Carrier, Richard (2014) "The Prospect of a Christian Interpolation in Tacitus, Annals 15.44" Vigiliae Christianae, Volume 68, Issue 3, pp. 264–283 (an earlier and more detailed version appears in Carrier's Hitler Homer Bible Christ)

- ↑ Carrier, Richard (2014) On the Historicity of Jesus Sheffield Phoenix Press Template:ISBN p. 344

- ↑ Tacitus on Christ#Christians and Chrestians

- ↑ Blom, Willem JC. "Why the Testimonium Taciteum Is Authentic: A Response to Carrier." Vigiliae Christianae 73.5 (2019): 564–581.

- ↑ Jesus, University Books, New York, 1956, p.13

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 75.4 75.5 75.6 75.7 The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 Template:ISBN p. 110

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 Evidence of Greek Philosophical Concepts in the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian by Ute Possekel 1999 Template:ISBN pp. 29–30

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 77.3 Studying the Historical Jesus: Evaluations of the State of Current Research edited by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1998 Template:ISBN pp. 455–457

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence by Robert E. Van Voorst 2000 Template:ISBN pp. 53–55

- ↑ Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies by Craig A. Evans 2001 Template:ISBN p. 41

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 Lives of the Caesars by Suetonius, Catharine Edwards 2001 Template:ISBN pp. 184. 203

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Birth of Christianity by John Dominic Crossan 1999 Template:ISBN pp. 3–10

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 82.5 Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. pp. 29–39

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire by Matthew Bunson 1994 Template:ISBN p. 111

- ↑ Christianity and the Roman Empire: background texts by Ralph Martin Novak 2001 Template:ISBN pp. 18–22

- ↑ R. T. France. The Evidence for Jesus. (2006). Regent College Publishing Template:ISBN. p. 42

- ↑ Louis H. Feldman, Jewish Life and Thought among Greeks and Romans (1996) Template:ISBN p. 332

- ↑ Template:About

Template:Selfref

Broadly, a citation is a reference to a published or unpublished source (not always the original source).[1] More precisely, a citation is an abbreviated alphanumeric expression (e.g. [Newell84]) embedded in the body of an intellectual work that denotes an entry in the bibliographic references section of the work for the purpose of acknowledging the relevance of the works of others to the topic of discussion at the spot where the citation appears. Generally the combination of both the in-body citation and the bibliographic entry constitutes what is commonly thought of as a citation (whereas bibliographic entries by themselves are not).

A prime purpose of a citation is intellectual honesty; to attribute to other authors the ideas they have previously expressed, rather than give the appearance to the work's readers that the work's authors are the original wellsprings of those ideas.

The forms of citations generally subscribe to one of the generally-accepted citations systems, such as the Harvard, APA, and other citations systems, as their syntactic conventions are widely-known and easily interpreted by readers. Each of these citation systems has its respective advantages and disadvantages relative to the tradeoffs of being informative (but not too disruptive) and thus should be chosen relative to the needs of the type of publication being crafted. Editors will often specify the citation system to use.

Bibliographies, and other list-like compilations of references, are generally not considered citations because they do not fulfill the true spirit of the term: deliberate acknowledgement by other authors of the priority of one's ideas.

Concepts

- A bibliographic citation is a reference to a book, article, web page, or other published item. Citations should supply sufficient detail to identify the item uniquely.[2] Different citation systems and styles are used in scientific citation, legal citation, prior art, and the arts and the humanities.

- A citation number, used in some citation systems, is a number or symbol added inline and usually in superscript, to refer readers to a footnote or endnote that cites the source. In other citation systems, an inline parenthetical reference is used rather than a citation number, with limited information such as the author's last name, year of publication, and page number referenced; a full identification of the source will then appear in an appended bibliography.

Citation content

Citation content can vary depending on the type of source and may include:

- Book: author(s), book title, publisher, date of publication, and page number(s) if appropriate.[3][4]

- Journal: author(s), article title, journal title, date of publication, and page number(s).

- Newspaper: author(s), article title, name of newspaper, section title and page number(s) if desired, date of publication.

- Web site: author(s), article and publication title where appropriate, as well as a URL, and a date when the site was accessed.

- Play: inline citations offer part, scene, and line numbers, the latter separated by periods: 4.452 refers to scene 4, line 452. For example, "In Eugene Onegin, Onegin rejects Tanya when she is free to be his, and only decides he wants her when she is already married" (Pushkin 4.452-53).[5]

- Poem: spaced slashes are normally used to indicate separate lines of a poem, and parenthetical citations usually include the line number(s). For example: "For I must love because I live / And life in me is what you give." (Brennan, lines 15–16).[5]

Unique identifiers

Along with information such as author(s), date of publication, title and page numbers, citations may also include unique identifiers depending on the type of work being referred to.

- Citations of books may include an International Standard Book Number (ISBN).

- Specific volumes, articles or other identifiable parts of a periodical, may have an associated Serial Item and Contribution Identifier (SICI).

- Electronic documents may have a digital object identifier (DOI).

- Biomedical research articles may have a PubMed Identifier (PMID).

Citation systems

Broadly speaking, there are two citation systems:[6][7][8]

Note systems

Note systems involve the use of sequential numbers in the text which refer to either footnotes (notes at the end of the page) or endnotes (a note on a separate page at the end of the paper) which gives the source detail. The notes system may or may not require a full bibliography, depending on whether the writer has used a full note form or a shortened note form.

For example, an excerpt from the text of a paper using a notes system without a full bibliography could look like this:

- "The five stages of grief are denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance."1

The note, located either at the foot of the page (footnote) or at the end of the paper (endnote) would look like this:

- 1. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying (New York: Macmillan, 1969) 45–60.

In a paper which contains a full bibliography, the shortened note could look like this:

- 1. Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying 45–60.

and the bibliography entry, which would be required with a shortened note, would look like this:

- Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth. On Death and Dying. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

In the humanities, many authors use footnotes or endnotes to supply anecdotal information. In this way, what looks like a citation is actually supplementary material, or suggestions for further reading.[9]

Parenthetical referencing is where full or partial, in-text citations are enclosed within parentheses and embedded in the paragraph, as opposed to the footnote style. Depending on the choice of style, fully cited parenthetical references may require no end section. Alternately a list of the citations with complete bibliographical references may be included in an end section sorted alphabetically by author's last name.

This section may be known as:

- References

- Bibliography

- Works cited

- Works consulted

Citation styles

Citation styles can be broadly divided into styles common to the Humanities and the Sciences, though there is considerable overlap. Some style guides, such as the Chicago Manual of Style, are quite flexible and cover both parenthetical and note citation systems.[8] Others, such as MLA and APA styles, specify formats within the context of a single citation system.[7] These may be referred to as citation formats as well as citation styles.[10][11][12] The various guides thus specify order of appearance, for example, of publication date, title, and page numbers following the author name, in addition to conventions of punctuation, use of italics, emphasis, parenthesis, quotation marks, etc., particular to their style.

A number of organizations have created styles to fit their needs; consequently, a number of different guides exist. Individual publishers often have their own in-house variations as well, and some works are so long-established as to have their own citation methods too: Stephanus pagination for Plato; Bekker numbers for Aristotle; citing the Bible by book, chapter and verse; or Shakespeare notation by play, act and scene.

Some examples of style guides include:

Humanities

- The American Political Science Association (APSA) relies on the Style Manual for Political Science, a style often used by political science scholars and historians. It is largely based on that of the Chicago Manual of Style.

- The ASA style of American Sociological Association is one of the main styles used in sociological publications.

- The Chicago Style (CMOS) was developed and its guide is The Chicago Manual of Style. Some social sciences and humanities scholars use the nearly identical Turabian style. Used by writers in many fields.

- The Columbia Style was made by Janice R. Walker and Todd Taylor to give detailed guidelines for citing internet sources. Columbia Style offers models for both the humanities and the sciences.

- Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace by Elizabeth Shown Mills covers primary sources not included in CMOS, such as censuses, court, land, government, business, and church records. Includes sources in electronic format. Used by genealogists and historians.[13]

- Harvard referencing (or author-date system) is a specific kind of parenthetical referencing. Parenthetical referencing is recommended by both the British Standards Institution and the Modern Language Association. Harvard referencing involves a short author-date reference, e.g., "(Smith, 2000)", being inserted after the cited text within parentheses and the full reference to the source being listed at the end of the article.

- MLA style was developed by the Modern Language Association and is most often used in the arts and the humanities, particularly in English studies, other literary studies, including comparative literature and literary criticism in languages other than English ("foreign languages"), and some interdisciplinary studies, such as cultural studies, drama and theatre, film, and other media, including television. This style of citations and bibliographical format uses parenthetical referencing with author-page (Smith 395) or author-[short] title-page (Smith, Contingencies 42) in the case of more than one work by the same author within parentheses in the text, keyed to an alphabetical list of sources on a "Works Cited" page at the end of the paper, as well as notes (footnotes or endnotes). See The MLA Style Manual and The MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, particularly Citation and bibliography format.[14]

- The MHRA Style Guide is published by the Modern Humanities Research Association (MHRA) and most widely used in the arts and humanities in the United Kingdom, where the MHRA is based. It is available for sale both in the UK and in the United States. It is similar to MLA style, but has some differences. For example, MHRA style uses footnotes that reference a citation fully while also providing a bibliography. Some readers find it advantageous that the footnotes provide full citations, instead of shortened references, so that they do not need to consult the bibliography while reading for the rest of the publication details.[15]

Law

- The Bluebook is a citation system traditionally used in American academic legal writing, and the Bluebook (or similar systems derived from it) are used by many courts.[16] At present, academic legal articles are always footnoted, but motions submitted to courts and court opinions traditionally use inline citations which are either separate sentences or separate clauses.

- The legal citation style used almost universally in Canada is based on the Canadian Guide to Uniform Legal Citation (aka McGill Guide), published by McGill Law Journal.[17]

Sciences, mathematics, engineering, physiology, and medicine

- The American Chemical Society style, or ACS style, is often used in chemistry and other physical sciences. In ACS style references are numbered in the text and in the reference list, and numbers are repeated throughout the text as needed.

- In the style of the American Institute of Physics (AIP style), references are also numbered in the text and in the reference list, with numbers repeated throughout the text as needed.

- Styles developed for the American Mathematical Society (AMS), or AMS styles, such as AMS-LaTeX, are typically implemented using the BibTeX tool in the LaTeX typesetting environment. Brackets with author’s initials and year are inserted in the text and at the beginning of the reference. Typical citations are listed in-line with alphabetic-label format, e.g. [AB90]. This type of style is also called a "Authorship trigraph."

- The Vancouver system, recommended by the Council of Science Editors (CSE), is used in medical and scientific papers and research.

- In one major variant, that used by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), citation numbers are included in the text in square brackets rather than as superscripts. All bibliographical information is exclusively included in the list of references at the end of the document, next to the respective citation number.

- The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) is reportedly the original kernel of this biomedical style which evolved from the Vancouver 1978 editors' meeting.[18] The MEDLINE/PubMed database uses this citation style and the National Library of Medicine provides "ICMJE Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals -- Sample References".[19]

- The style of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), or IEEE style, encloses citation numbers within square brackets and arranges the reference list by the order of citation, not by alphabetical order.

- Pechenik Citation Style is a style described in A Short Guide to Writing about Biology, 6th ed. (2007), by Jan A. Pechenik.[20]

- In 2006, Eugene Garfield proposed a bibliographic system for scientific literature, to consolidate the integrity of scientific publications.[21]

Social sciences

- The style of the American Psychological Association, or APA style, published in The Style Manual of the APA, is most often used in social sciences. APA style uses Harvard referencing within the text, listing the author's name and year of publication, keyed to an alphabetical list of sources at the end of the paper on a References page

- The American Political Science Association publishes both a style manual and a style guide for publications in this field.[22]

- The American Anthropological Association utilizes a modified form of the Chicago Style laid out in their Publishing Style Guide

See also

- Acknowledgment (creative arts)

- Bible citation

- Case citation

- Citation creator

- Citation signal

- Citationality

- Credit (creative arts)

- Cross-reference

- Scholarly method

- Source evaluation

- Style guide

Footnotes

References

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2172: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web (2nd ed.)

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite web

- Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2172: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

External links

- Guidelines

- Citing Government Documents/Government Agency Style Manuals, University of North Texas Libraries.

- Document it Citation and Referee AMS, and the AMSRefs package.

- Guide to Citation Style Guides

- ONLINE! Citation Styles (An online guide to different citation formats)

- "What is citation?", Turnitin.com

- Examples

- Illustrated examples, generated using BibTeX, of several major styles, including more than those listed above.

- PDF file bibstyles.pdf illustrates how several bibliographic styles appear with citations and reference entries, generated using BibTeX.

- Style guides

- AMA Citation Style